AMD is closing in on Intel with its Epyc CPUs. On the GPU front, the company is challenging Nvidia with Instinct. However, networking – part of AMD’s next push – requires a novel approach. Collaboration rather than confrontation is key in this arena.

“The only way to meet demand is to grow on every front.” That’s what Soni Jiandani, SVP & GM Network Technology Solutions Group at AMD, has concluded. He is referring to the fact that AMD needs to think beyond the CPUs and GPUs it has become known for. At its own Advancing AI event in San Francisco, networking is remarkably prominent in the AMD story. Indeed, it’s fundamental to everything it does.

Also read: Avalanche of new AMD products: Epyc, Instinct, Ryzen and more

The “third pillar”

This fact is most clearly verbalized by Forrest Norrod, EVP & GM of the Datacenter Solutions Group inside AMD. He explains in detail how AMD’s positioning in the data center world has become broader than ever. Epyc, the beating heart of compute, has been taken from “virtually zero” back in 2017 to a 34 percent revenue share last quarter. AMD’s gain is Intel’s pain, whose problems we’ve described in detail over the past few months. With Epyc’s latest fifth generation, it enters the fray against Xeon 6, a competitor which AMD promises to beat in the benchmarks overall.

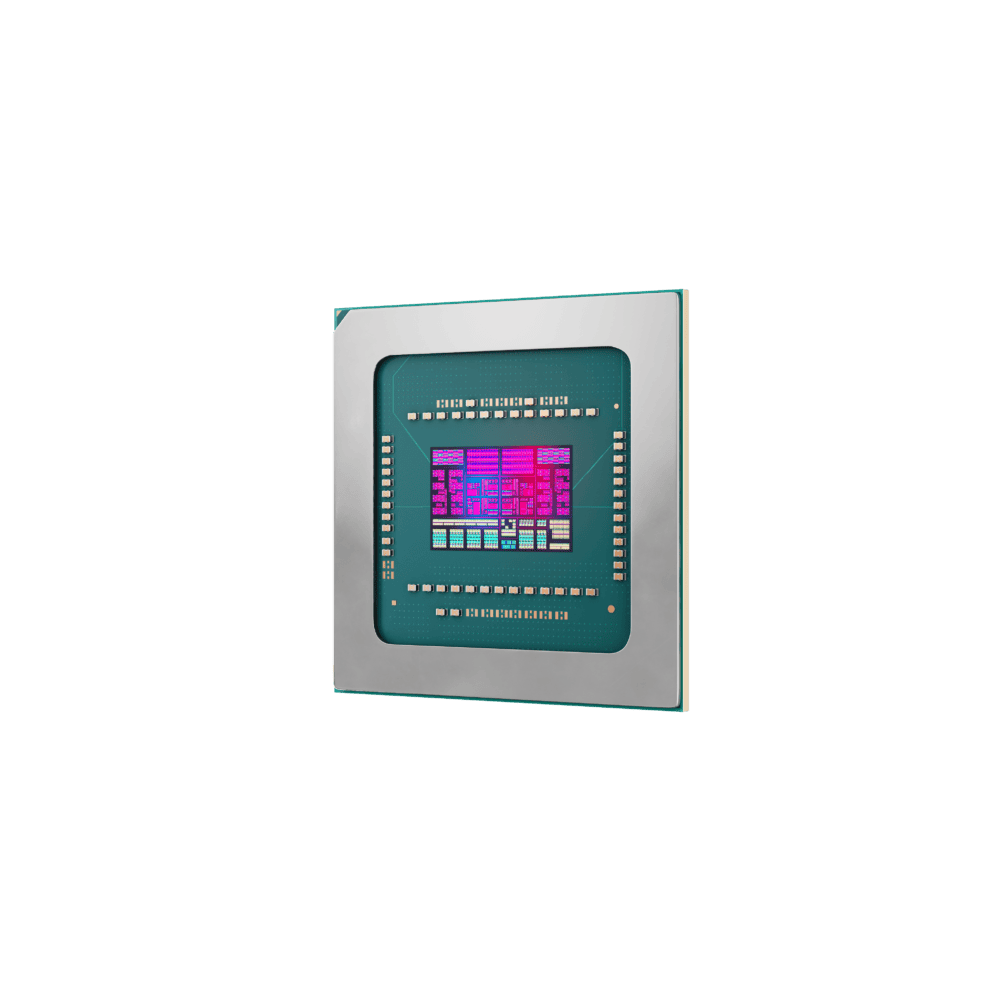

A far more formidable rival has turned out to be Nvidia. The latter’s success has stretched credulity, rocket-boosting itself to a 3 trillion market cap aided by a data center GPU market share of just under 100 percent. Nevertheless, AMD has achieved 115 percent revenue growth in the meantime in the data center segment last quarter, something it says it owes mainly to the ongoing ramp of Instinct GPUs. This is its own alternative to Nvidia’s H100 chips and also versus its rival’s up-and-coming Blackwell. Currently, MI300X has been available for roughly a year, the souped-up version (MI325X) just launched and MI355X is the next step intended for mid-2025. Some time later, MI400 should take on Nvidia’s as-yet elusive Rubin line of products.

But it doesn’t stop there. Norrod says there is a third pillar to be placed under AMD’s foundation: networking. This is because AI is straining the network in unprecedented ways. And while AMD has its own chip to aid this process, too, it wouldn’t be enough to only discuss said product.

The network has to flow

The problem networks are facing are as follows. AI is reshaping the traffic patterns of workloads, placing completely unprecedented demands on heretofore inconspicuous parts of the network. Front-end networks suddenly are having to cope with heaps of data coming in from the outside world, while said data is frequently of a sensitive nature and thus in need of heavy protection. Specifically, the workloads cause a hodgepodge of downloads, uploads and checkpoints at an ultra-rapid pace. At the same time, the back-end network must scale up to thousands (or even more than a million, more on that later) of GPUs and distribute heaps of data as well and divvy it up. To top it off, whenever a problem arises, traffic flows turn into traffic jams within microseconds.

Additionally, the explosion of AI workloads requires different infrastructure choices, in which a CPU is essentially just a head node for GPUs. It incentivizes customers to push for more GPU real estate at the expense of the central processors that have laid claim to said space for decades. “The pressure on CPUs for AI workloads is often underexposed,” Norrod says, countering any suggestion it has lost its relevance for the in vogue use-case. And this lack of exposure creates problems, because an overloaded CPU wonn’t utilize the GPUs that depend on it.

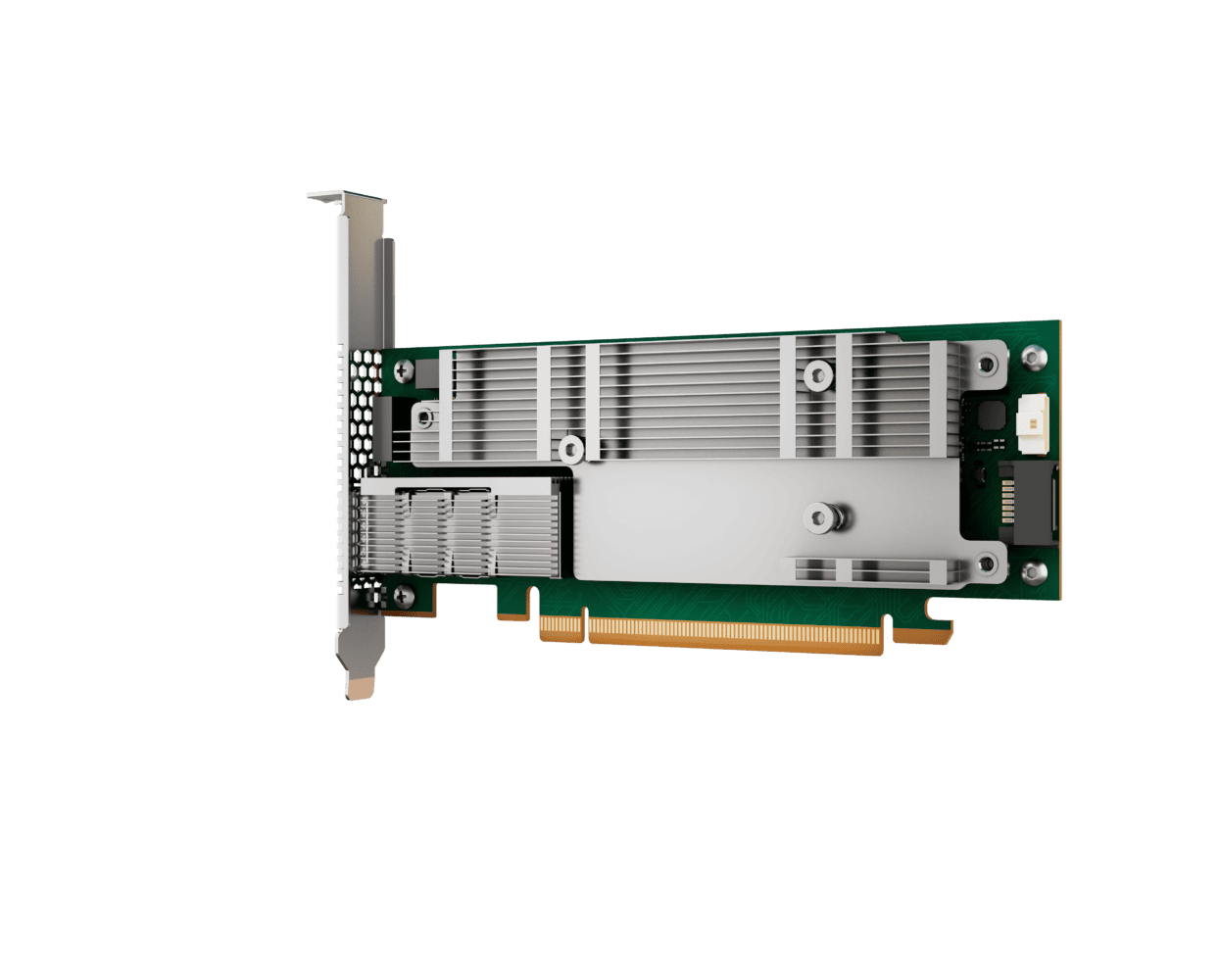

All this means that the CPU needs breathing room. Just as the graphics card was once created to spare the CPU, the Data Processing Unit (DPU) was created to outsource its particular kind of rotework to a discrete chip. Since the AMD acquisition of Pensando in 2022, such a DPU has been in the former’s portfolio, with the brand-new version being the Salina 400.

Pensando portfolio

“Every packet hits the DPU,” Narayan Annamali, GM and Head of Product of Azure Networking at Microsoft, says on AMD’s stage at its Advancing AI event. He explains that the DPU is about much more than throughput. Applying security policies, for example, is an essential function of the Pensando chip. That requires an advanced piece of silicon “designed for hyperscalers,” according to AMD. On board are 232 MPU engines (match processing units), which control connections and packets instead of the CPU threads having to process them.

Another Pensando product is the Pollara 400, an NIC that optimizes network utilization itself. Jiandani talks about the need to maximize back-end network utilization. For example, Meta found that when it came to AI training, the company spent 30 percent of the time waiting on the back-end. “Any kind of delay stops the progress of the GPUs,” Jiandani says. “As a result, you lose extremely valuable information.” Or to put it another way: you lose time (i.e. money) and money. And this truly is just a case of throwing cash down the drain: there’s zero benefit. The Pollara 400 should ensure this malady occurs as little as possible, and it will make use of the network in a smarter, more efficient way than its predecessors.

What does a regular NIC do at the end of the day? It performs a fallback to an old checkpoint in the event of a network error and retransmits a bunch of data, adding network traffic insult to packet loss injury. To go from the current 50 percent utilization to 95 percent and eliminate this redundancy, AMD says we need a new weapon. The Pollara 400 is exactly that in a variety of ways, providing intelligent load balancing as well as automatically bypassing network congestion anywhere. In short: while the Salina 400 gets data through as quickly as possible, the Pollara 400 ensures this high-speed traffic doesn’t meet a standstill.

Tip: Cognizant and Palo Alto Networks partner on security services

The old familiar Ethernet

Ultimately, this is still, in a sense, a refinement of what we know. But some say we need to go further. And we’re not just talking about a slight bump to the GPU count at the expense of CPUs. Nvidia’s CEO Jensen Huang says we need “AI factories” in which the CPU-to-GPU ratio becomes ludicrously lopsided. With the aforementioned dominant market share, one might expect Nvidia to hold sway here. Does the market really care to follow? And what’s the blowback if it doesn’t?

AMD isn’t coming out and saying it, but it’s deeply skeptical about this approach. Indeed, it says it’s actually advantageous to stick with familiar approaches. That, at least, is the desire of the Ultra Ethernet Consortium, founded 1.5 years ago. Its 97 members include many tech giants, including co-founders AMD, Broadcom, Cisco, Intel and Microsoft. An Ultra Ethernet Spec, 1.0, which outlines exactly how Ethernet should run optimally for AI workloads, will also follow in the first quarter of 2025. As it happens, Nvidia is also a member, but its motives are hard to gauge. It is championing InfiniBand as the faster, more modern alternative for AI/GPU networking,.

According to the EUC, Ethernet is in fact the communication medium of the future. A major advantage of Ethernet is that it is already everywhere. Unlike InfiniBand, a favorite of Nvidia for tethering GPUs, the old infrastructure will still be usable for state-of-the-art AI workloads. “It’s clear that Ethernet is the winner in terms of scalability as well as performance,” Jiandani says. Since everyone is training a state-of-the-art AI model on a distributed system with numerous GPUs, that scalability is extremely important.

How do you achieve that scalability? InfiniBand has a limit of 48,000 GPUs. With Ethernet, it is possible to scale up beyond a million “without dramatic and very complex workarounds,” according to AMD. Here the company is referring to the need to build a three-layer network rather than one with just two when using InfiniBand with more than 48,000 GPUs. This is due to an architectural choice. However, Ethernet does simply result in more latency between GPUs down the line, so it’s not surprising that AMD is tieing this story closely to the Pensando DPUs and NICs that in turn mitigate this problem. What you get in return is the option to move away from AMD if you prefer Intel or Nvidia accelerators, whenever that may occur – you can still use Ethernet there. The same is categorically not true with Nvidia’s InfiniBand.

Giving choice

This all hooks nicely into a broader aspect of AMD’s success story. It can credibly claim to give customers freedom of choice. First, this is evidenced by its adherence to Ethernet versus the closed-off world of InfiniBand. But we also know about AMD’s behaviour in other situations. Take Epyc for example, which switches CPU sockets less often than Intel’s Xeon chips, allowing users to upgrade at a lower cost. Or Ryzen, which stayed on AM4 motherboards forever (with a recent new release even though AM5 is already two years old) for consumers while Intel has gone through CPU sockets at a rather puzzling pace.

Choice also exists within the newest AMD portfolio: an Epyc chip with powerful 5GHz boosting cores is available on the same platform as a variant with 192 efficient Zen 5c cores. There is also no specific advantage for customers combining AMD CPUs with its own GPUs and/or DPUs, meaning users get to pick and choose vendors at every turn.

The key question is whether this will ever change. AMD’s recent acquisitions (of Silo AI and ZT Systems) make this more likely than before. European Silo AI is an asset to the company in terms of AI expertise, in part because of the 100+ PhD holders within that company. American server builder ZT Systems signifies a more explicit move toward full-stack AI solutions, in which networking plays a crucial role. However open and traditional the Ethernet situation may be, if you end up buying an entire system from AMD with all the company’s CPUs, GPUs and DPUs in one marked-up solution, you’re as single-vendored as you would have been with Nvidia’s DGX options. Granted, we’re a long way away from any such development, we think.

Conclusion

Norrod isn’t shying away from AMD’s strategy in the here and now, anyway. Obviously, a chipmaker wants to sell chips. But he emphasizes that AMD’s growth, so firmly initiated after its near-vanquished state a decade ago, has now entered a new stage. Now established as a major CPU player and GPU challenger, the company wants to enable end-to-end AI without stepping on others’ toes. It needs allies to big up networking on Ethernet for AI workloads. That’s not going to change. It is also unrealistic to expect the company to start dominating both the CPU and GPU markets anytime soon. Epyc’s growth, however explosive it has been toward 34 percent, for example, has already leveled off as companies continue to run their existing systems longer. If AMD ends up overtaking Intel’s share in the data center CPU space, it will be a gradual pass rather than a rocket boost.

Perhaps this story is a bit less fun for investors than elsewhere. Nvidia keeps promising and delivering faster AI chips, end of story. AMD’s diversified approach means it cannot make bold claims in quite the same way, even though its actual progress ranges from steady to astounding.

Nevertheless, words cannot describe the contrast between AMD in 2024 and the company a decade ago. In the server area, the advance actually took place only five years ago, so just a little longer than a refresh cycle for data center chips (three to four years). AI is now forcing the company to push ahead with both GPUs and networking chips. In this new situation, Norrod emphasizes that AMD wants to continue to provide customers with choice. That’s a big promise.

Reading tip: Qualcomm’s latest networking chip runs local AI workloads